-

Polina Berlin Gallery is pleased to announce We prayed and prayed and nobody listened, Loral Raphael’s debut exhibition with the gallery, on view from November 19 through December 13, 2025.

Known for his work in music composition, Raphael emerges here as an energetic painter of allegorical narratives and expressionistic gestures. Through a series of densely textured works in oil, Raphael conjures a feverish theatre of human behavior with both caustic wit and profound empathy. Indicative of the breadth of Raphael’s multidisciplinary practice, this body of paintings is accompanied by a recording of a poem written by the artist’s brother and frequent collaborator Ronnel Raphael, recited by the actress and musician Charlotte Gainsbourg.

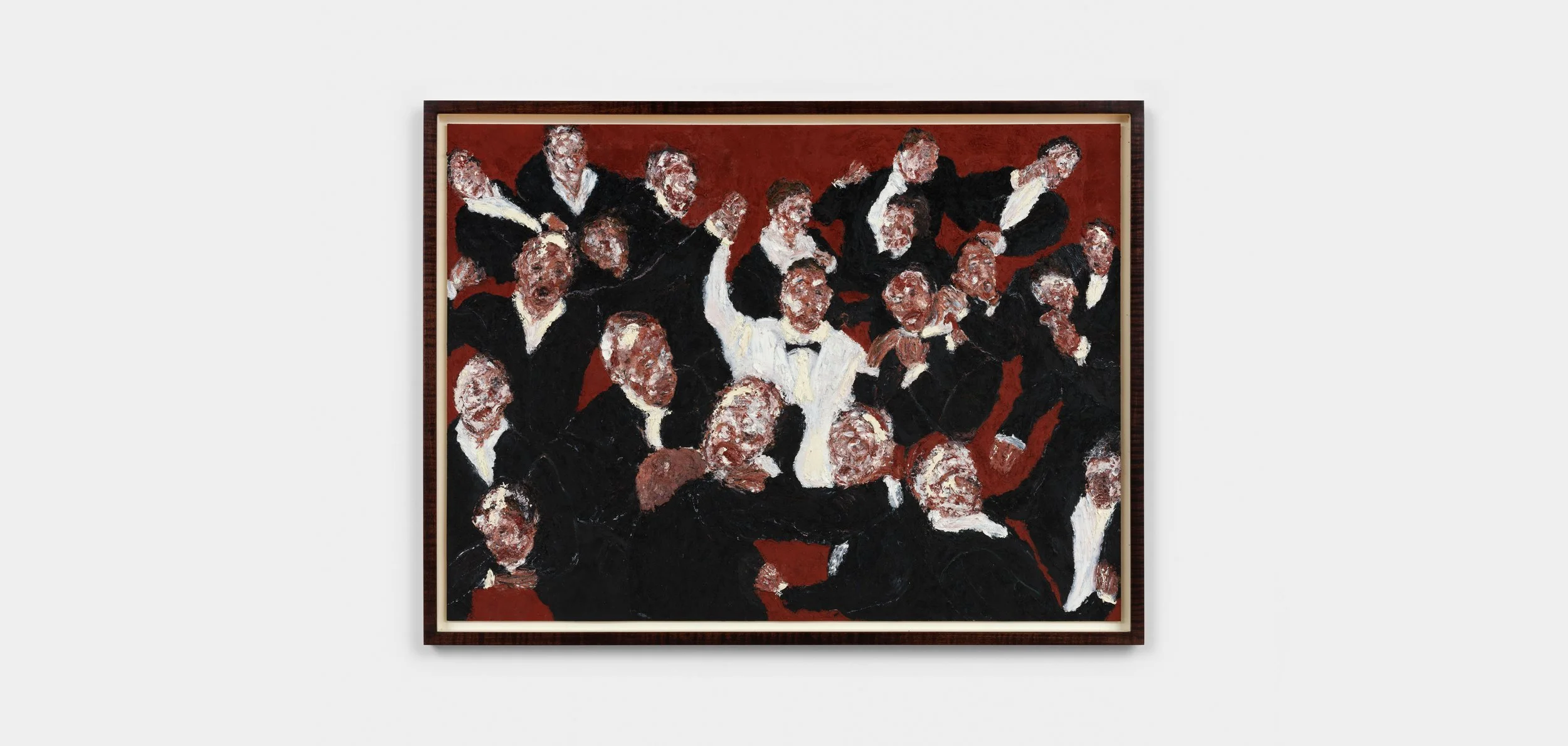

Produced during a period in which the artist was also creating orchestral compositions, the works on view were made in hotel rooms and other temporary spaces distinct from the traditional artist’s studio. In some sense, they function within the artist’s broader practice as a reprieve from the demands of working collaboratively, opening space for solitary expression within a practice often marked by the challenges and negotiations of making creative work with others. Yet it would be wrong to suggest that these paintings abandon the concerns and contentions of Raphael’s work in music; it would be more accurate to suggest they sublimate the fraught sensations of interpersonal conflict and translate the dramatic capacities of music into visual form. In paintings such as Now He Belongs to the Ages and The Arm of Those Who All Fight, the artist constructs a melodious, cross-sensory experience through dynamic compositions replete with swelling crescendos and subtle dénouements, both of which, allude to the orchestra. Minimally rendered, the orchestra hall itself appears as a recurrent setting, even if, by an associative dream logic, this setting may transform into a parliamentary chamber or a racetrack, a black-box theatre or a portal to heaven. As in the operating theatre paintings of Thomas Eakins, Raphael often includes audiences and spectators within his compositions, extending an early modernist understanding of looking and watching that implicates the viewers, too.

While the action of these works unfolds within a conceptual framework of staged performance and mediated spectacle, it is also clear that this framework is deployed in service of trenchant allegories concerning human relations and the organization of society. Perhaps intuiting a correspondence between the early twentieth century and the current moment, the artist draws upon a lineage of Expressionism rooted in existential angst, reimagining a sense of figurative distortion and ambient estrangement engendered by artists such as Edvard Munch, Chaïm Soutine, and Francis Bacon. There are perhaps traces of Leon Golub as well in Raphael’s depictions of stylized violence, particularly in works like My God, My God, What Will The Country Say?, although Raphael’s scenes appear unmoored from both torn-from-the-headlines subjects and the specificities of the quotidian world; they recast typologies and narratives drawn from Western culture and place them within an alternate reality. Archetypal figures – whether the pious or sinners, American football players or horse jockeys – clash against one another in vibrant, harmonious compositions, subjects and situations reappear across successive works. Together, they generate a kaleidoscopic narrative of dissolution that remains fragmented, that emerges or re-emerges in unexpected moments. Even in a painting like A Work for 33 String Players, which at first seems to be a candid group portrait of string musicians, Raphael has partially embedded a quote from Spinoza on an overhanging banner: “Peace is not an absence of war, it is a virtue, a state of mind, a disposition for benevolence, confidence, justice.” Benevolence, confidence, justice – it is precisely this disposition, these values, that the events rendered by Raphael’s paintings call into question.

Collectively, these paintings depict a Machiavellian world on the brink of collapse, situating the breakdown of social order in a much broader context, or otherwise vivifying what Raphael suggestively considers “the tearing of the temple curtain.” The separation of God from man is another preoccupation of Raphael’s paintings, one which provides the exhibition with some of its most poignant moments of comic absurdity. Yet the curtain’s rending may also serve as a metaphor for art’s immediacy, its potential to create a direct relationship between work and viewer. For all their stylistic obfuscations, Raphael’s paintings make a strong case for this form of directness, a visceral argument for an art concerned with timeless and common themes, with enduring questions filtered through the trick mirror of personal, subjective experience. -

Loral Raphael (b. 1992) lives and works in London. He earned his BA from King's College London (2015-18). In addition to painting, Raphael has been producing music with his brother Ronnel Raphael under the moniker Sons of Raphael. The duo recently released their debut record, Full-Throated Messianic Homage and composed the original music for Sofia Coppola's feature film Priscilla. Raphael is currently making new music with Thomas Bangalter of Daft Punk.