-

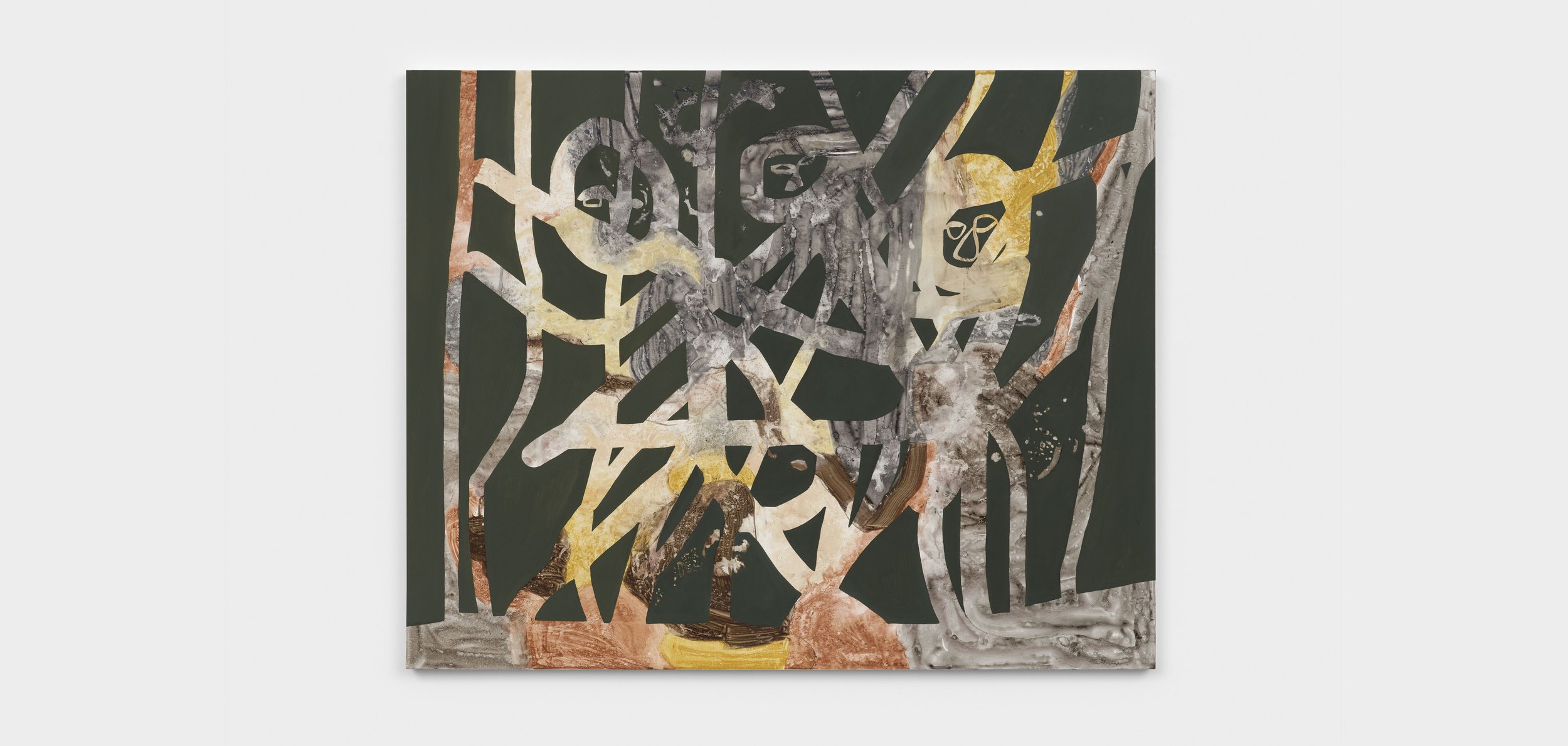

Polina Berlin Gallery is pleased to present Lichtenberg Figure, the gallery’s debut exhibition with multidisciplinary artist Brian DeGraw. As a visual artist, musician and DJ, DeGraw has developed a singular practice centered around improvisation and sampling, folding myriad stylistic devices, as well as cultural and autobiographical references, into each work. Lichtenberg Figure comprises a body of paintings in which the artist finds himself rethinking his approach to figuration, shifting closer toward a mode of freewheeling abstraction and intuitive graphic interplay. To complement the exhibition, DeGraw has organized a series of live performances with his colleagues and fellow musicians hosted at the gallery, which will unfold on select Saturdays throughout the show’s duration.

Encompassing his music and visual art practice, DeGraw’s method is rooted in the improvised assemblage of materials both found and created by the artist. Fragments of text, images of anthropological objects, album cover art, and original sketches are all among the source materials embedded within the painting’s architecture, and like the process of his music making, the aggregation is purely spontaneous. Resisting any kind of categorization, his paintings oscillate between the structured elements of representation and the instinctive happenstance of abstraction. Collaged-like layers of visual references, lyrical undertones, and transcendental patterns are culled together in a generative balance between free association and methodical revision. The works that emerge from this orderly process unearth latent connections and memories that reflect the diversity and whim of the lived experience. DeGraw’s impulse for improvisation that lies beneath each composition can become a touch point for the relationship between music and life, art and music, and life and art.

DeGraw begins by applying a layer of heavily diluted acrylic and flashe and letting it take form and harden into a tactile base layer. This improvised ground becomes the site of formal excavation: using a distinctly hard-edged top-layer, DeGraw lets faces, instruments, geometric shapes and hints of natural life emerge in a state of rhythmic entanglement. Much like his musical process, in which synths, drums, piano trills or frantic booms are let to form their own continuity, the assemblages refuse to be reduced to an easily recognizable authorial hand. Instead, each composition thrums with the unpremeditated desire toward discovery that guided it. As in Harpist (after LMB), a marbled pastel ground is treated with maroon and grisaille oil. A knelt-down figure materializes at the center of the picture, maybe praying, but the medley of abstract negations begins to cohere: the knelt-down woman appears to be surrounded by trees, plucking the strings of a harp. From under the veneer of hard-edged abstraction, something like a Trecento fresco emerges.

“Lichtenberg figures are not made, they are received”, DeGraw said when discussing the title of the show. In DeGraw’s practice, nature assumes the role of the artist – the way it produces, strikes and lives without authorship or correction. The body, like the raw canvas, becomes a passive ground, and his quiet process of painting becomes permitting rather than controlling. The collection of works in the exhibition mirrors the spiritual ideas of the artist as a vessel rather than the creator, allowing questions about will, chance and identity to come to the fore.

-

Brian DeGraw (b.1974, Meriden, Connecticut) lives and works in New York. He has recently presented solo exhibitions at James Fuentes, Los Angeles (2024), and New York (2022, 2011, 2007); Soccer Club Club, Chicago (2023); Wish-Less, Tokyo, Japan (2019), and Allen & Eldridge, New York (2015). He most recently presented a two-person exhibition alongside Maria Naveriani at Tanya Leighton, Berlin, Germany (2024). His work has been included in group exhibitions at Polina Berlin Gallery, New York (2024); Pace Gallery, New York (2023, 2022); Gallery Artbeat, Tbilisi, Georgia (2023); Galerie Julien Cadet, Paris, France (2023), amongst others. His work has been presented in institutional exhibitions at The Jewish Museum, New York (2015); Macro Future Museum, Rome, Italy (2009); Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (in the 2008 Whitney Biennial); Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, Austria (2007); and Deste Foundation, Athens, Greece (2007, 2006). DeGraw’s work resides in the public and private collections of The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Dakis Joannou Collection; Agnés B Collection; Zabludowicz Collection; LAC Collection; Madeira Corporate Services Collection; and Ragnarock Museum, Roskilde, Denmark. DeGraw is a founding member of the experimental music group Gang Gang Dance. Notable performances with Gang Gang Dance include The Museum of Modern Art: Judson Dance Theater; 88 Boadrum; Sydney Opera House; Pitti Uomo; Brandt Foundation; and the Brooklyn Academy of Music, in collaboration with Alice Coltrane.

-

Born

Meriden, CT, 1974. Lives and works in New York, NY

One-Person Exhibitions

2026 Lichtenberg Figure, Polina Berlin Gallery, New York, NY (2/11-3/14)

2024 SP555, James Fuentes, Los Angeles, CA (12/11-2/8)

2023 Thank You Dean Blunt, Soccer Club Club, Chicago, (9/30-10/27)

2022 Gamma, James Fuentes, New York NY (8/15-9/17)

2019 Solarium Demos, Wish-Less, Tokyo, Japan (1/26-2/17)

Scratch Acid Ketosis, Real Estate Fine Art, Brooklyn NY (5/25-6/29)2015 Brian DeGraw, Allen & Eldridge, New York NY (6/24–7/3)

2011 As The World Burns, James Fuentes, New York NY (6/1-7/2)

2008 Solo Exhibition, Le Confort Moderne, Poiters, France

2007 Behead the Genre, James Fuentes, New York NY (1/27-2/28)

2004 Solo Exhibition, Dazed Gallery, London UK

2002 Danger Came Smiling, The Annex/Aaron Rose, Los Angeles CA

2001 Brian DeGraw (curated by Bjarne Melgaard), UKS Galleri, Oslo, NO (3/30-4/22)

Solo Exhibition, Sub Commandante Marcos, Oslo, NorwaySelected Group Exhibitions

2024 Brian DeGraw & Maia Naveriani: Works on Paper, Tanya Leighton, Berlin, DE (10/9-11/9)

The rose is the rose and is the cat, Polina Berlin Gallery, NY (6/4-8/2)

Emotional Intelligence II, Polina Berlin Gallery, NY (2/22-3/27)2023 The Rejectionists, Pace Gallery, New York, NY (10/25-11/8)

Consensual Ennui,The Landing Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (9/22-11/18)

The Painting Show, ArtBeat Gallery, Tbilisi, Georgia (7/21-9/3)

Le Langage Du Corps– Collection agnés B, La Fab , Paris, FR (6/9-11/12)

Evening of the Day, Galerie Julien Cadet, Paris, FR (4/28-6/3)

Emotional Rescue, Galleria Annarumma, Napoli, IT (12/10-1/23)2022 10 Years, Wish-Less, Tokyo, JP (11/26-12/11)

New York Eye & Ear Control, Boo-Hooray, Montauk, NY (7/29-8/9)

Unsafe At Any Speed (curated by Kenny Schacter), Morton Street Partners, New York, NY

Twenty One Humors, Pace Gallery, New York, NY (3/15-5/8)2021 It’s Not What You Think It Is, Tramps, New York, NY (4/28-5/28)

New Wave Cosmos, Wish-Less, Tokyo, JP (5/1-5/16)2020 Travelers Perspective, Colossal Youth Exhibitions, Brooklyn, NY (2/16-3/29)

2019 Meet Me in the Bathroom, The Hole, New York, NY (9/4-9/22)

2018 Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY (9/16-2/3/2019)

New York by Night (curated by Spencer Sweeney), HdM gallery, Beijing, CN (3/23-5/6)

Benders, Real Estate Fine Art, Brooklyn, NY (6/9-9/1)2017 Peace Pieces (with Spencer Sweeney), Hysteric Glamour, Tokyo, JP (1/28-2/12)

Drawing Island, The Journal Gallery, Brooklyn, NY (2/16-2/26)

SIGH, The LODGE Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (4/1-5/6)2016 Ry Fyan and Brian DeGraw, Allen & Eldridge, New York, NY (6/24-6/29)

Inoshikacho: the Boar, the Deer, and the Butterflies, Ace Hotel, New York, NY2015 Unorthodox, The Jewish Museum, New York, NY (11/6-3/27/2016)

Slam Section (curated by Leo Fitzpatrick), Steinsland Berliner, Stockholm, SE (4/17-5/15/2016)

Hotels, Loyal Gallery, Malmö, SE (3/25-5/30)2014 This is Our Art This is Our Music, David Risley Gallery, Copenhagen, DK (2/21-3/5)

2012 Do Your Thing, White Columns, New York, NY (6/9-714)

2011 MusIQUE, PlastIQUE, galerie du jour agnès b., Paris, FR (1/28-4/2)

2009 New York Minute, Macro Future Museum, Rome, IT (9/20-11/1)

2008 The Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (3/6-6/1)

2007 Dream & Trauma, Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, AT (6/29-10/4)

The Fractured Figure (curated by Jeffrey Deitch and Dakis Joannou), Deste Foundation, Athens, GR (9/5-7/31/2008)

The Process VI, Swiss Institute, New York, NY (3/21-5/1)2006 Panic Room - Works from The Dakis Joannou Collection (curated by Kathy Grayson and Jeffrey Deitch), Deste Foundation, Athens, GR (2/2-4/4/2007)

The Rest is Total Silence, ATM Gallery, New York, NY (7/6-7/28)

The Process IV, Stinftung Binz39, Zurich, CH (1/21-218)2004 Reverberations (curated by James Fuentes), Gavin Brownʼs Enterprise at Passerby, New York, NY

Indigestible Correctness Part II, (curated by Lizzi Bougatsos and Rita Ackermann), Kenny Schachter/ROVE, New York, NY

The Human Face is an Empty Force, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, NL (1/24-2/28)

Giles Deacon, Steven Shearer, and Brian DeGraw, Roma Roma Roma, Rome, IT

Concrete Castle (curated by Rita Ackermann), Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers, FR (9/24-12/11)

The Process II (as part of the exhibition Fürchte dich), Helmhaus, Zürich, CH (2/13-4/12)

What’s New (curated by Rita Ackermann), Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, NL(11/27-1/15/2005)

Kitty Ex. 30 Years of Hello Kitty Anniversary Exhibition, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, JP (7/31-8/28/2005)2003 The Process, Neue Kunsthalle, St. Gallen, CH (9/6-11/9)

New York Dirty, Gallery Claska, Tokyo, JP

A New York Scene, galerie du jour agnès b, Paris, FR (9/18-10/24)

Survival of the Shittest (curated by James Fuentes), The Proposition, New York, NY

Culture Keeps Model Brain Handy Made of Its Grain to Put in the Place of Your Own, American Fine Arts Co., New York, NY2002 Little America, New Image Art, Los Angeles, CA

High Times (with Spencer Sweeney), Hysteric Glamour, Tokyo, JP2001 Sunshine, Alleged Gallery, New York, NY

Precious Cargo, KBond, Los Angeles, CA

Welcome to the Playground of the Fearless (curated by James Fuentes), Entropy, Brooklyn, NY2000 God Bless America, Alleged Gallery, New York, NY

1999 Dope: An XXX-Mas Show, American Fine Arts, New York, NY (12/22-1/8/2000)

Residencies

2025 | Residency, Dragon Hill, Mouans-Sartoux, FR

2023 | Residency, superzoom, Ardéche, FR

2008 | Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers, FR

Notable CollectionsThe Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

Dakis Joannou Collection, Athens, GR

North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks, ND

Agnés B. Collection, Paris, FR

Zabludowicz Collection, London, UK

LAC Collection

Madeira Corporate Services Collection, Madeira, PT

Ragnarock Museum, Roskilde, DK